My son in law's great grandfather, Leonard Harold Glenister, 1904-1995, was a merchant seaman. So when Find My Past released their new collection of Merchant Navy records last week I looked him up.

The records are index cards created by the Registrar General of Shipping and Seamen for all those serving on British merchant navy vessels from 1918 to 1941. The front of each card contains biographical information plus a description and, if you are lucky, there is a photograph on the back, together with details of ships on which the person served.

I duly found a card for him, covering the period 1918 to 1921. He joined the merchant service as a "Deck Boy" in 1918, aged 14. He was only 4 foot 7 inches in height, with light brown hair and grey eyes. He looked very solemn and worried in his photograph.

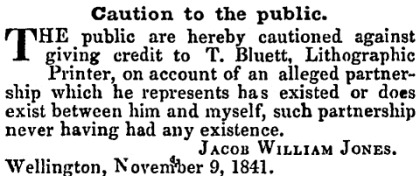

Find My Past have included a helpful link to the Crew List Index Project, to identify the names of ships from the official numbers used on the index cards. From CLIP I learned that Leonard's first ship, which he joined on 23 January 1919, was the SS Zealandic. Constructed by Harland and Wolff in Belfast, she was launched in 1911 and owned by the White Star Line, of Titanic fame. Her home port was Liverpool. In 1917 she was commandeered by the Royal Navy for the transportation of troops and was still being used for that purpose when Leonard joined her, sailing between Liverpool and Wellington in New Zealand. Troops returning home were carried in one direction and meat from New Zealand in the other.

On 13 January 1920, Leonard moved to his second ship, SS Athenic, also owned by the White Star Line. She was a passenger liner, built in Belfast by Harland and Wolff and launched in 1901. She carried 121 passengers in first class, 117 second class and 450 third class. The ship was equipped with electric lighting and cooling chambers for the transport of frozen lamb. Like the Zealandic, she sailed on the New Zealand route.

Leonard Glenister's voyage on the Athenic turned out to be rather eventful. I have pieced together the following account of what happened from newspaper reports in the United States and New Zealand.

On her outward journey from London to Wellington, via the Panama Canal, the Athenic was carrying 500 homebound New Zealand soldiers. On 2 February they were docked in Newport News, Virginia, where an influenza epidemic was raging. The soldiers were forbidden to go ashore but 50 of them defied the order. Their commanding officer promptly reported them to the local police and they were arrested as deserters. According to the newspaper report, "They resented the charge of being deserters, but were herded back to their ship without difficulty after a brief stay in the police station". Athenic was due to sail the following day but was kept in port for a further three days by a fierce storm which brought 50 mph winds and huge waves.

The return journey was even more dramatic. On Sunday 2 May 1920, an American steamer, the SS Munamar, on a voyage from Antilla, Cuba to New York, ran aground on a reef off San Salvador Island in the Bahamas. The ship was in a very dangerous position and taking on water fast, so the passengers were all put into the lifeboats. Athenic was in the vicinity and received Munamar's SOS call about 9pm. The first Athenic's passengers knew of the incident was when her engines suddenly stopped. It was too dark to effect a rescue but fortunately it was a calm night, so the Munamar's passengers sat in their lifeboats, whilst the Athenic circled, waiting for dawn. At daybreak on 3 May the 83 passengers from the Munamar were rescued, and their baggage and the mails salvaged from the stranded ship. The whole operation took about two hours.

Athenic had a full passenger list and no empty berths, so the Captain ordered beds to be made up in the public rooms for the new arrivals. Unfortunately, this led to an ugly display of racism. 30 of the rescued passengers were black and the other Munamar passengers objected strongly to sharing accommodation with them. They "made a great many complaints" but the Captain of the Athenic stood firm. No doubt all concerned were very relieved when the Athenic landed the Munamar's passengers at Newport News, three days later. From there they made their way to New York by train.

The Munamar was eventually floated off the reef, after 2,000 bags of sugar from her cargo were thrown overboard, and taken to a dry dock in Jacksonville, Florida, for repairs. She then returned to service between Cuba and New York. Some time later, Captain Crossland of the Athenic was given a gold watch by President Warren Harding, in recognition of his ship's rescue efforts.