It was the evening of Friday, 30 June 1837 and William Tomlin was outside his house at Newcastle Coal Wharf, Limehouse, London. William was a prosperous, self-made man, the owner of a fleet of lighters and barges which transported coal and timber from ships in the Thames at Limehouse up the Regent's Canal.

Being high summer, it was still very light when, around 8pm, William saw four youths sitting on a grassy bank about 100 yards away. They were pointing at William's house excitedly, in a way which aroused his suspicions. He watched them for nearly an hour and called his wife and son to take a look at them, saying that, if his house was broken into, these young men would be the people to do it. They did not realise they were under observation, because William and his family were hidden by some trees.

When William went to bed at 11pm, he made sure that he locked up well. Nevertheless, sometime after midnight the youths managed to break into the house through the kitchen window, using a knife to dig out the putty so that they could partially remove the glass and undo the catch. They then reached their hands over the top of the shutters to unfasten them. Once in the house they stole:

-

a £20 banknote;

-

two silver table-spoons, five tea-spoons and a mustard-spoon, valued at £2 12s;

-

two pairs of spectacles, valued at £2;

-

a coat, valued at £1 10s;

-

three silk handkerchiefs, valued at 9s;

-

a pair of shoes, valued at 5s;

-

a silver thimble, valued at 1s; and

-

two fourpenny pieces.

The total value of £26 17s 8d would be the equivalent of over £2,000 today.

William Tomlin was woken around 3am on Saturday, 1 July, and found the desk from his sitting room lying outside on the Wharf. It had been broken open with two chisels which lay nearby. Several papers, the £20 bank-note and the two fourpenny pieces were missing from it. One of the fourpenny pieces was very distinctive because William had bored a hole through it with a drill, in an attempt to place it on a ring.

Meanwhile, the burglars had not gone far with their haul. At about 4.30 am a brick maker found the four of them asleep in the straw in his brickfield, a short distance from William Tomlin's house. He threw them out and, in leaving, two of them made the mistake of passing close to the scene of the crime. They were recognised by William, who gave chase and caught up with them about 400 yards away, in Salmon Lane, Limehouse. He pointed them out to a policeman and they were arrested.

The two were John Burton, aged 17, and George Williamson, aged 18. Samuel Weatherstone, aged 16, a known associate of Burton and Williamson, was arrested on Monday, 3 July, having been spotted loitering outside the police station. The police found these three in possession of most of the stolen property. Burton had a table spoon up each sleeve, the handkerchiefs under his shirt and the shoes on his feet. Williamson had the two pairs of spectacles and the silver thimble and he was wearing the coat under his own clothes. Weatherstone had 14s in his pocket and the fourpenny piece with the hole in it on a scarlet ribbon round his neck. The fourth accomplice was never traced.

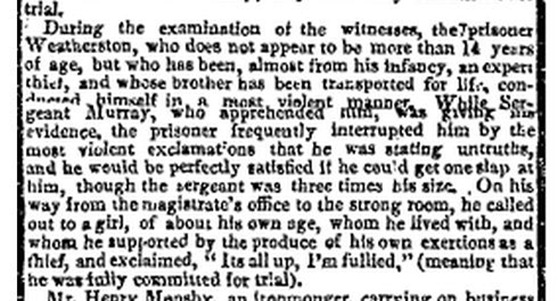

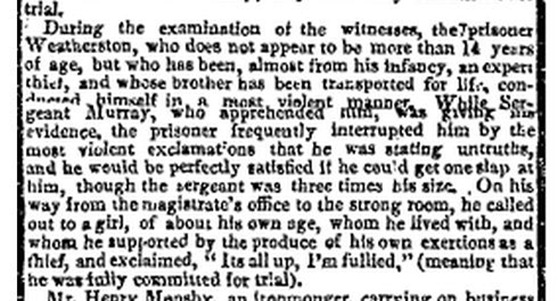

Weatherstone, Burton and Williamson were brought up before the magistrates for examination on Tuesday, 4 July. According to a reporter from the Times:

The three were tried for burglary at the Old Bailey the next day, Wednesday 5 July 1837. The evidence against them was overwhelming but, in order to avoid the death penalty for burglary, the jury found them guilty of the lesser charge of breaking and entering. All three were sentenced to be transported for life.

Samuel George Weatherstone sailed on the convict ship Earl Grey from Portsmouth on 27 July 1838, arriving in New South Wales in November. He was granted a ticket of leave in 1846 and pardoned in 1849. He remained in Australia, where he married Letitia Doherty and had six children. He died in Grafton, New South Wales, in 1888, aged 70. By the time of his death he and his family owned considerable amounts of land and cattle.

George Williamson was transported on the ship Lord William Bentinck, departing from Portsmouth on 14 April 1838. He arrived in Tasmania on 26 August. His transportation documents record that he was tattooed with a mermaid and anchor, which suggests he was a sailor. In 1841 he was working for Mr J McArthur in Launceston, Tasmania. By 1846 he had a ticket of leave and by 1849 he had been granted a conditional pardon. He married a fellow convict, Hannah Tillotson, in Launceston in October 1846. According to a descendant, George and Hannah "settled down, raised a family and became good, solid citizens".

John Burton, who was lame, had his life sentence commuted to seven years. He was transported on the convict ship Asia, departing from London on 25 April 1840 and arriving in Tasmania on 6 August. In 1841 he was working in a party of convicts at Southport in the extreme south of Tasmania. By 1846 he was free on a certificate.

From the mistakes they made before and after their crime, it is hard to believe these three were the professional thieves that Weatherstone, at least, was made out to be. Almost certainly they were driven to steal by extreme poverty. Today they would not even be sent to prison for a first offence of this nature, yet in 1837 these three young men only escaped the gallows because of the clemency of the jury.

Life in the hulks during the long months waiting for transportation must have been utterly ghastly. Penal servitude probably only slightly less so. Yet, following their release, two at least were successful in the new, young country of Australia. Their punishment was unbelievably harsh but it removed them from the squalor and misery of poverty in London's East End and, in the end, turned out to be the gateway to a new and better life.

Postscript

My connection to these three young men is that William Tomlin was my husband's 4x great grandfather. William died in London on 15 June 1850, survived by 10 of his 11 children. He left nearly £45,000 in his will - at a conservative estimate, the equivalent of over £4 million today.

I initially learned about this case from a report in the Times dated 5 July 1837, which I found online in the Times Digital Archive. I then found the report of the Old Bailey trial at the Old Bailey Online website. I found information about the transportation and subsequent lives of the three young men on Ancestry, in both the historical records and the member trees.

I wish all my Australian cousins a very happy Australia Day. Here in the UK our thoughts and prayers are very much with you in the aftermath of the recent terrible floods.

They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old:

They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old: